商品編號:DJAP47-A900FUHQY

A Self-Made Man(精裝)

驚喜優惠

$474

$600

- 登記送

【7-11】單筆滿$350純取貨/取貨付款訂單登記送香鑽水果茶兌換券乙張(限量)

- 登記送

【OK】單筆滿$1純取貨/取貨付款訂單登記送OK購物金30元(限量)

- 登記送

App限定-全站指定單筆滿$2500登記送雙11獨享券(限量/效期2024/11/4~11/12)

付款方式

- 信用卡、無卡分期、行動支付,與其他多種方式

- PChome 聯名卡最高6%,新戶再享首刷禮1000P

出貨

配送

宅配滿$490免運,超取滿$350免運

- 宅配到府(本島/低溫)滿$699免運

- 宅配到府(本島/常溫)滿$490免運

- 超商取貨(常溫)滿$350免運

- 超商取貨(低溫)滿$699免運

- i郵箱(常溫)滿$290免運

銀行卡、行動支付

優惠總覽

商品詳情

作者: | |

ISBN: | 9786267189436 |

出版社: | |

出版日期: | 2023/01/01 |

內文簡介

<內容簡介>

憑藉著對語言的熱情,在新聞界殺出一條路,造就了此本濃縮人生精華的全英文自傳。

他出生於中國湖北省的貧困農家,隨著中國淪陷於共產黨勢力手中,跟隨軍隊來台。

到達高雄港時,他只帶了一張草墊和兩套破舊的軍服……

抱著極大熱忱,在18年軍隊服役過程中自學英文,

退伍後,開啟了於《中國郵報》的記者生涯,

在離開新聞採訪與編輯崗位之後,

隨即替《英文中國郵報》、《中國經濟通訊社》撰寫精闢的政論與專欄,

以敏銳的眼光見證台灣經濟局勢與民主化的蛻變……

★目錄:

Introduction

Chapter 1 Falling Leaves Return to Their Roots

Chapter 2 Revisiting a Wartime Fort 60 Years On

Chapter 3 A Decade of Change

Chapter 4 Starting a Career in Journalism at 33

Chapter 5 A Brief Foray into Chinese-language Journalism

Chapter 6 My Second China Post Stint

Chapter 7 Hired as Asian Sources Taiwan Bureau Chief

Chapter 8 Joining China Economic News Service

Chapter 9 Switching to Commentary Writing

Chapter 10 How I Assess Ex-President Chen Shui-bian

Afterword

<作者簡介>

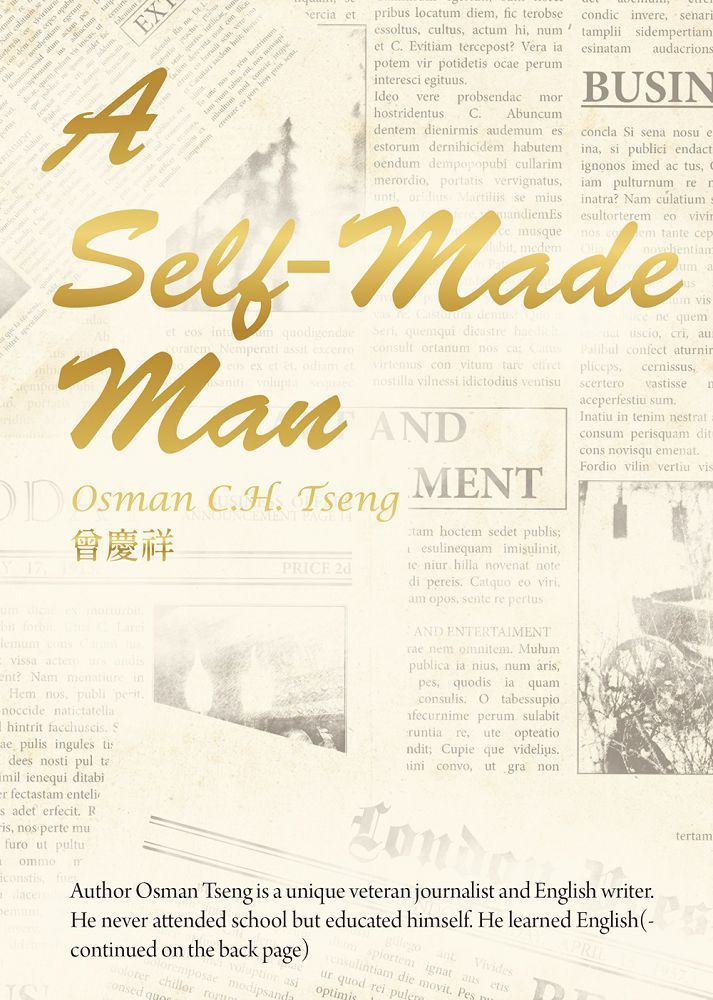

Author Osman Tseng is a unique veteran journalist and English writer. He never attended school but educated himself. He learned English in the army where he served for 18 years since he was in his mid-teens. He started his career in English-language journalism at the age of 33 and stuck with the profession until his retirement 45 years later. He always learns on the job, while practicing journalism. Through it all, he has always been reading and writing.

★內文試閱:

‧作者序

Introduction

I was a little bit hesitant at first to choose the term A Self-Made Man for the title of this book--my autobiography. A self-made man generally refers to an individual who rises to success from humble origins through his efforts. I was hesitant because I was not sure how to define success. Nor was I sure about how much success was required to deem someone a successful person. In my case, I wondered whether my modest accomplishments could be considered a successful life. I am still unsure about that. On reflection, I chose to call my autobiography the story of A Self-Made Man, leaving the above question to the readers to judge after they finish my account.

I think I do meet the other element of being a self-made man: rising from humble origins. I was born in 1933 into a farming family in a small Chinese village beside the Yangtze River. My parents owned a small farm that allowed them to grow just enough to feed our family members. Both of my parents were uneducated. They could not read or write.

I received only six years of village school education in my life. Unlike primary schools in the educational system in the bigger cities, those village institutions taught only Chinese. No other subjects, like math or a foreign language, were part of the curriculum. But even this limited formal education was disrupted by the disastrous Yangtze River floods in 1947. Due to the significant damage from the flooding, my parents could no longer afford to continue funding my schooling. Without their financial support, I finally chose to join the army despite my young age. Although soldiers were poorly paid at the time, they at least had enough to eat.

I was only 16 years old when I came to Taiwan with the military in mid-1949. This was about the time Chiang Kai-shek and his government and military forces retreated to the island following the fall of the mainland to the communists. I remember when I disembarked from a ship in the southern port of Kaohsiung, my only personal belongings were a straw mattress and two sets of worn-out army fatigues.

In Taiwan, I served the next 18 years in grassroots infantry companies, rising from private to captain. I used my free time in the military to study English, which is not my native tongue. I started learning the ABCs at the age of 20.

I studied English the hard way. In the first 10 years or so of my studies, I pressed ahead with my task in army bunkers, barracks, or in the field. I spent weekends and all other available time studying this difficult language. The only learning aid I had was a Chinese-English dictionary.

Yet I had never anticipated that my rudimentary style of learning would be so fruitful that it enabled me to pass a crucial test 13 years later, allowing me to join an English-language newspaper as a reporter. At this point, I was 33 years old.

What I also never imagined was that English would become a language tool for me to practice journalism for the next half-century. I wrote news reports, features, commentaries, and editorials in English. And after I retired from the journalism profession, I also used this acquired language to write my autobiography as well as a book about former President Chen Shui-bian during his eight years in office.

Furthermore, I never expected that I would be able to achieve the status of a professional journalist, given my lack of formal education and journalism training. It was very fortunate for me that I was able to climb up the ladder of journalism. During my decades-long career in this field, I played various key roles from reporter to city editor, editor-in-chief, and editorial writer.

The successes of my effort to study English and my striving to become a professional journalist and writer were made possible, simply put, by hard work, perseverance, and a strong passion for journalism and English writing.

The story of A Self-Made Man, Osman C.H. Tseng, is a chronicle of my life and career. It recounts important events in my life. The story consists of 10 chapters, as set out below.

‧推薦序

Note from an Old Friend

Veteran journalist Osman C.H. Tseng has had a front-row seat to many of the crucial events that have shaped modern Taiwan and thrust it into the global spotlight. Over the years, he has been a sharp-eyed observer of Taiwan's economic coming of age and its transformation from authoritarian rule to a vibrant democracy. In his autobiography A Self-Made Man, he traces the compelling story of his own journalistic career and offers his keen observations of key political figures and the policies they put in place.

His personal story is an unlikely one. Born into a poor farming family in China's Hubei province, he joined Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist (Kuomintang) army as a teenager, following it to Taiwan as the mainland fell to advancing Communist forces. He arrived at the port of Kaohsiung with only a straw mattress and two sets of worn-out army fatigues.

During his nearly two decades in the army, he taught himself English starting with the ABCs and aided by little more than a battered Chinese-English dictionary and a deep well of determination. That ultimately paid off as he qualified as an army interpreter and later, after the conclusion of his military service, landed an entry-level reporting job with the English language daily newspaper, the China Post.

This is where he began to acquire the fundamental journalistic skills of gathering facts, ensuring accuracy, and making careful observations of events. His career path led him to the helm of one of Taiwan's foremost business news organizations, the China Economic News Service, where he also crafted editorials and commentaries.

Fittingly, his career took him back to the China Post once again, where he continued to hone his skills as an opinion writer. His widely read commentaries for these two media organizations ranged from the ambitious democratic reforms of Lee Teng-hui, Taiwan's first popularly elected president, to the policy chaos under his successor, Chen Shui-bian, eventually jailed for corruption.

A Self-Made Man will be of interest to journalists and non-journalists alike. Its publication is particularly timely in an era of pervasive accusations of "fake news" that have undermined the traditional respect for the profession of journalism in the public eye. Hopefully, this account of how a persistent individual overcame considerable odds to follow a passion for journalism will contribute to restoring some of that public trust.

William Kazer

‧摘文

Chapter 4

Starting a Career in Journalism at 33

Striving to Make up for a Lack of Journalistic Training

I reported to the China Post for work on January 5, 1966, as agreed on. I gained admission to the English-language newspaper after I passed both a written exam and a face-to-face interview. At the time I was still in the military. But I agreed with publisher Nancy Yu-Huang in the interview that I would apply for retirement if I passed a six-month training period and my employment with the newspaper became official.

In the end, I went through the training program, and the China Post formally hired me. I thus applied to my military unit for retirement. My application was granted. So I left the army, ending my nearly two decades of military service. This was truly a life-altering moment: Making a career change in my early 30s, from nearly two decades of military service to journalism, a profession which I was never trained for.

From day one, I constantly faced two big challenges. One was how to gather news worth reporting. The other was how to write English news stories that were readable. As I said earlier, English is not my native tongue, and I began to learn it at the age of 20.

In all, I gathered news and wrote news articles for around a dozen years, accounting for one-fourth of my total journalism career. After leaving the reporting job, I served in several other positions that involved me editing news stories and writing commentaries until my retirement. Performing well in the roles of editing and commentary writing was no less challenging. It demanded profound English knowledge and high-level writing skills.

In other words, the challenges I faced in this latter stage of my journalism career remained strong. I had to continuously work hard and put in long hours to improve my capabilities to ensure that I could measure up to my editing and commentary writing responsibilities.

It can be said that working hard and continuing to learn were the hallmarks of my decades of journalism life.

My trial employment period at the China Post began with the start of a six-month “reserve reporters” training seminar, sponsored by the newspaper. The purpose of the seminar was manifest in its name. Classes were offered twice a week. I was an obligatory attendee. During the six-month period, I came to work for the Post daily, from 6:30 p.m. to midnight, while continuing to work for my military unit in the daytime.

I was assigned to assist in the running of the seminar. Besides me, there were five other attendees. Among them was Alice Sun, who like me was formally accepted and offered a job. Miss Sun, however, was designated as an assistant to the publisher, not working in the editorial department as I was. The remaining four candidates all had participated in the same reporter-recruitment test but failed to pass it. However, they were put on the waiting list. But somehow they were never formally employed.

Attendees to the seminar were taught news-gathering and news-writing skills, as well as journalistic duties and ethics. Lecturers included Taipei bureau chiefs stationed by major international news agencies, such as UPI (United Press International), AP (Associated Press), AFP (Agence France-Press), and Reuters. These veteran journalists and writers were invited to lecture on journalism and share their practical experiences with us.

Among other lecturers was Nancy Yu-Huang, the Post publisher. Nancy Yu-Huang held journalism degrees from Yenching University in Beijing, China, and Columbia University in the City of New York, United States. She taught us the value of the classic “Five W’s and One H” of Journalism. They stand for six questions: What happened? Who was involved? Where did it take place? When did it occur? Why did that happen? And How did it happen? Answers to these questions are considered basic in gathering news or writing news stories. A news story failing to address any of these questions was viewed as incomplete. So the “Five W’s and One H” were held as the basic guidance for journalism practitioners.

相關分類

購物須知

| 寄送時間 | 全台灣24h到貨,遲到提供100元現金積點。全年無休,週末假日照常出貨。例外說明 |

|---|---|

| 送貨方式 | 透過宅配送達。除網頁另有特別標示外,均為常溫配送。 消費者訂購之商品若經配送兩次無法送達,再經本公司以電話與Email均無法聯繫逾三天者,本公司將取消該筆訂單,並且全額退款。 |

| 送貨範圍 | 限台灣本島與離島地區註,部分離島地區包括連江馬祖、綠島、蘭嶼、琉球鄉…等貨件,將送至到岸船公司碼頭,需請收貨人自行至碼頭取貨。注意!收件地址請勿為郵政信箱。 註:離島地區不配送安裝商品、手機門號商品、超大材商品及四機商品。 |

| 售後服務 | 缺掉頁更換新品 |

| 執照證號&登錄字號 | 本公司食品業者登錄字號A-116606102-00000-0 |

關於退貨

- PChome24h購物的消費者,都可以依照消費者保護法的規定,享有商品貨到次日起七天猶豫期的權益。(請留意猶豫期非試用期!!)您所退回的商品必須回復原狀(復原至商品到貨時的原始狀態並且保持完整包裝,包括商品本體、配件、贈品、保證書、原廠包裝及所有附隨文件或資料的完整性)。商品一經拆封/啟用保固,將使商品價值減損,您理解本公司將依法收取回復原狀必要之費用(若無法復原,費用將以商品價值損失計算),請先確認商品正確、外觀可接受再行使用,以免影響您的權利,祝您購物順心。

- 如果您所購買商品是下列特殊商品,請留意下述退貨注意事項:

- 易於腐敗之商品、保存期限較短之商品、客製化商品、報紙、期刊、雜誌,依據消費者保護法之規定,於收受商品後將無法享有七天猶豫期之權益且不得辦理退貨。

- 影音商品、電腦軟體或個人衛生用品等一經拆封即無法回復原狀的商品,在您還不確定是否要辦理退貨以前,請勿拆封,一經拆封則依消費者保護法之規定,無法享有七天猶豫期之權益且不得辦理退貨。

- 非以有形媒介提供之數位內容或一經提供即為完成之線上服務,一經您事先同意後始提供者,依消費者保護法之規定,您將無法享有七天猶豫期之權益且不得辦理退貨。

- 組合商品於辦理退貨時,應將組合銷售商品一同退貨,若有遺失、毀損或缺件,PChome將可能要求您依照損毀程度負擔回復原狀必要之費用。

- 若您需辦理退貨,請利用顧客中心「查訂單」或「退訂/退款查詢」的「退訂/退貨」功能填寫申請,我們將於接獲申請之次日起1個工作天內檢視您的退貨要求,檢視完畢後將以E-mail回覆通知您,並將委託本公司指定之宅配公司,在5個工作天內透過電話與您連絡前往取回退貨商品。請您保持電話暢通,並備妥原商品及所有包裝及附件,以便於交付予本公司指定之宅配公司取回(宅配公司僅負責收件,退貨商品仍由特約廠商進行驗收),宅配公司取件後會提供簽收單據給您,請注意留存。

- 退回商品時,請以本公司或特約廠商寄送商品給您時所使用的外包裝(紙箱或包裝袋),原封包裝後交付給前來取件的宅配公司;如果本公司或特約廠商寄送商品給您時所使用的外包裝(紙箱或包裝袋)已經遺失,請您在商品原廠外盒之外,再以其他適當的包裝盒進行包裝,切勿任由宅配單直接粘貼在商品原廠外盒上或書寫文字。

- 若因您要求退貨或換貨、或因本公司無法接受您全部或部分之訂單、或因契約解除或失其效力,而需為您辦理退款事宜時,您同意本公司得代您處理發票或折讓單等相關法令所要求之單據,以利本公司為您辦理退款。

- 本公司收到您所提出的申請後,若經確認無誤,將依消費者保護法之相關規定,返還您已支付之對價(含信用卡交易),退款日當天會再發送E-mail通知函給您。